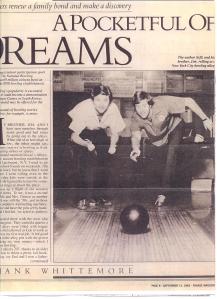

FAME 2009 the movie failed to live up to the original FAME of 1980, and the TV show that followed, but I figure it’s time to reprint my PARADE article in 1982 on the real-life “Fame School” — the High School of Performing Arts in New York City.

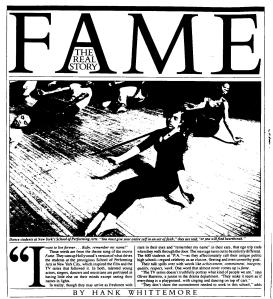

FAME – The Real Story

PARADE – August 22, 1982

By Hank Whittemore

“I want to live forever . . . Baby, remember my name!”

Those words are from the theme song of the movie Fame. They sum up Hollywood’s version of what drives the students at the prestigious School of Performing Arts in New York City, which inspired the film and the TV series that followed it. In both, talented young actors, singers. dancers and musicians are portrayed as having little else on their minds except seeing their names in lights.

In reality, though they may arrive as freshmen with stars in their eyes and “remember my name” in their ears, that ego trip ends when they walk through the door. The message turns out to be entirely different. The six hundred students at “P.A.” – as they affectionately call their unique public high school – regard celebrity as an elusive, fleeting and even unworthy goal.

Their talk spills over with words like achievement, commitment, integrity, quality, respect, work. One word that almost never comes up is fame.

“The TV series doesn’t truthfully portray what kind of people we are,” says Oliver Barreiro, a junior in the drama department. “They make it seem as if everything is a playground. with singing and dancing on top of cars.”

“They don’t show the commitment needed to work in this school,” adds Caren Messing, another acting student. “They’re very result-oriented. All you see are these musical numbers, with kids performing all the time. But we deal with the process and the practice.”

The film did capture the highly competitive audition process required for admission – out of about 4500 annual applicants, only 200 new students are accepted – and the school’s balanced racial mix. “This is a school where black kids, white kids, Puerto Rican kids, yellow kids and all the others come together to be liberated,” says Jerry Eskow, chairman of the drama department. “In a real sense, they are all breaking out of their individual

ghettos.”

One of the graduates this year is Erica Gimpel, who took time off to play the leading role of Coco Hernandez in the Fame TV series. In a press release, MGM Television speaks of Coco’s “consuming hunger for success.” She “knows she’s bound for stardom and fame,” it adds. “It’s just a matter of when it will happen. Her choice is tomorrow … or sooner!”

The real Miss Gimpel is a serious acting student – not a dancer like Coco – and she could hardly wait to get back from Hollywood to continue her work at P.A. There she is treated as an equal, not as a celebrity. “Erica came back to school to find the reality,” Eskow says. He adds that, like her classmates who regularly watch her on Fame, “she understands the difference and feels just as strongly about work as they do.”

For Gene Anthony Ray, who played the role of Leroy Jobnson – a streetwise, resentful black dancer – in both movie and series, the difference between Hollywood and reality is perhaps more ironic. Ray had been a Performing Arts student, but he left the school without completing its program. In the screen version, however, Leroy is kept on and even treated as a special case.

“Now, that’s really unrealistic,” says Corinth Booker, a young black student and, like Leroy, a dancer. “And on the series, nobody wants to get on Leroy’s bad side because he’s so talented. Here, there’s just no kind of favoritism like that. Leroy gets away with being very stubborn and selfish, and he argues with teachers – like, ‘Are you telling me what I should do?’ That’s not the way it is.”

As head of the P.A. dance department, Lydia Joel resembles a strict but caring aunt. Her lecture to freshman dancers comes right to the point “This is an absolutely undemocratic situation you face. You have no rights here. Your only right is to come to class and be wonderful. You can’t protest, you can’t be absent, you can only work. If you are aspiring to work on the professional level, there is only quality, quality, quality. And we will help you be wonderful.”

“Dancing is an extraordinary human endeavor,” Joel tells her students. “We can try to find flexible bodies, vitality, response to instruction and the potential for achievement, but what we really can’t judge is your motivation. It’s like a little flame that burns inside of you. And no matter how much you want to be a big star, it won’t work if that fire doesn’t burn strongly enough to give you the patience and dedication you need. You must give your entire self in an act of faith. If you have any sort of resentment or lack of clarity, you will find heartbreak. But if you manage to live through four years of this

demand upon your inner self, your life will be literally changed.”

The students say that Hollywood’s depiction of competitiveness among them is unrealistic. “It seems like everyone is scratching their eyes out to beat each other out,” Oliver Barreiro says, “but that is just the opposite of how it works here. We don’t talk about each other behind our backs. We work together, all striving for the same thing.”

In a city loaded with crime, drugs and other problems involving teenagers, P.A. students insist that drug usage is far less here than at other high schools. “They have real respect for their bodies,” says Fred Wile, P.A.’s guidance counselor. “Just as you can’t be twenty pounds overweight and function as a dancer, you certainly can’t play Beethoven while you’re stoned on drugs.”

Long before Fame the movie brought Performing Arts into the national limelight, the school was known among professionals as the alma mater of such stars as Al Pacino, Lisa Minnelli, Ben Vereen, Melissa Manchester and the late Freddie Prinze. And to most of its illustrious graduates, the school is something very special. “I tell my freshmen students to go out and interview an actor or director,” Jerry Eskow says, “to find out what they feel is important. And even the biggest stars will talk to a kid from Performing Arts.”

Dustin Hoffman, Eskow recalls, was approached one time by a fourteen-year-old girl from the drama department. “Could you give me an interview?” she asked.

“No time,” Hoffman said.

“I’m from the School of Performing Arts.”

“Oh! Well, listen,” Hoffman replied, “I can’t do it now, but why don’t you come to my home tomorrow morning?”

When she arrived, Hoffman was still asleep, but he roused himself for the interview. The girl couldn’t get her tape recorder to work and started to cry. Hoffman helped her with the machine and even conducted the first half of the interview by asking himself questions until she overcame her shyness.

Another student approached George C. Scott at a time when the actor was refusing to talk to the press. As Scott emerged from a lobby in Lincoln Center, the young man tried to get his attention.

“What the hell do you want?” Scott roared in his familiar gruff voice.

“I’m from the School of Performing Arts.”

“Come on,” Scott barked, grabbing the student by the arm and marching him across the street to a drugstore. “Sit down,” he said, ordered coffee for them both and launched into a forty-minute interview as if it were the most important thing in the world.

Which, of course, it often is. The youngsters are being asked to look deep within themselves and come up by age seventeen with answers to the questions: “Do I have what it takes? Should I make this my whole life?”

“Talent is all around us,” Eskow says, “but the trick is to identify it and then help the students to see themselves as talented entities rather than as street kids.”

“Most schools see a student as an empty vessel to fill with knowledge,” he explains. “We believe that these kids are the reverse. You go to a medical school and come out a doctor. Here, the actor or dancer or musician already exists, and our job is to peel away the layers preventing that professional from emerging.”

At 6 a.m. on weekdays, dance student Corinth Booker wakes up in Harlem, does his chores, takes his little sister to a babysitter’s apartment and then rides the crowded subway down to the very different world of Performing Arts. He attends his classes, goes through muscle-numbing practice sessions, takes more dance classes on the side and works as a busboy three nights a week. He has his chance, yet he knows time is already running out.

“They want these young dancers out there,” says student Terri Hall. “It’s like, if you’re twenty, you’re old! I mean, at sixteen, I’m halfway over. I’m really so unsure about what want now. If I went to college, I wouldn’t major in dance because the level isn’t high enough. Should I stay in New York when I graduate? On the Fame series, you never see any of the characters going through these changes.”

Henry Rinehart, also sixteen, says he has lost his adolescence by having had to make his own way in the city while studying acting at P.A. His parents are separated, so he lives at another student’s apartment and copes on his own. “I’m supposed to be a teenager growing up.” he reflects, “but I look at myself and find that I’ve already done it.”

The reality, Henry says, is learning about failure: “They tell us, ‘If you’re going to fail, do it here and go all the way. Fail big!’ Because you learn so much from having to pick yourself up and go on. In deciding whether to continue as performers, we’re really experiencing how to face life.”

Nina LoMonaco, seventeen, is another part of the reality, practicing her French horn on the staircase, blowing it so loudly that the paint starts chipping and falling down all around her. While other young people are off having a good time, she studies and practices hour after hour. She says she often wonders: “My God, am I making the biggest mistake of my life? What am I doing this for?”

Should Nina skip regular college and try to become one of the best musicians in the country? “I can understand people getting discouraged,” she says, “but that’s fine because it’ll mean less competition for me. I’m going to reach as high as I can, and if I don’t make it, that’s my problem. But I have to take this chance. Now.”

Is the punishing life of a dancer the only way Corinth Booker can break out of Harlem and the urban jungle? How will Henry Rinehart know, really, if he has what it takes to be a professional actor? Does Terri Hall honestly want the life of a dancer to the exclusion of so much else?

In the real world, these youngsters are at the edge of adolescence, looking out at an unclear future. Yet they have to make decisions about leaping into it. They’re seeking an answer – some sort of message that will make them decide one way or another.

For Lydia Joel, the answer comes every day. As we sit in the tiny office from which she runs the dance department, the pounding of a practice piano underscores the sound of dancers practicing in a studio two floors above. In another room, a student orchestra plays. Down the hall, some acting students rehearse a scene from Euripides.

“These kids are beautiful in the right sense of the word,” Lydia Joel says. “The sounds of this school are the sounds of involvement.”

Then she picks up a postcard from a former dance student: “I would like to thank you for recommending me. I did very well at the audition and in made it to the last 15 out of 300 girls. But nothing came of it. Well, maybe next time. I’m not going to give up. I love it too much.”

She puts down the postcard. She sighs. “One very beautiful girl who was doing quite well came to me last year and told me she’d decided to become a nurse instead of a dancer. The flame inside her burned toward nursing. But here,” she points to the postcard, “the flame is toward the dance as a way of life. That’s how it burns.”

Flame – not fame – is the message.

///////////

Fame TV Show Cast:

Debbie Allen .…………. Lydia Grant

Gene Anthony Ray ………. Leroy Johnson

Carlo Imperato ………… Danny Amatullo

Albert Hague ………….. Mr. Benjamin Shorofsky

Ann Nelson ……………. Mrs. Gertrude Berg

Carol Mayo Jenkins …….. Elizabeth Sherwood (1982-1986)

Billy Hufsey ………….. Christopher Donlon (1983-1987)

Valerie Landsburg ……… Doris Rene Schwartz (1982-1985)

Bronwyn Thomas ………… Michelle (1982-1985)

Cynthia Gibb ………….. Holly Laird (1983-1986)

Jesse Borrego …………. Jesse V. Valesquez (1984-1987)

Nia Peeples …………… Nicole Chapman (1984-1987)

Lee Curreri …………… Bruno Martelli (1982-1984)

Morgan Stevens ………… David Reardon (1982-1984)

Ken Swofford ………….. Quentin Morloch (1983-1985)

Loretta Chandler ………. Dusty Tyler (1985-1987)

Graham Jarvis …………. Mr. Bob Dyrenforth (1985-1987)

Dick Miller …………… Mr. Lou Mackie (1985-1987)

Lori Singer …………… Julie Miller (1982-1983)

Erica Gimpel .………Coco Hernandez (1982-1983)

Dave Shelley ………….. Caruso (1983-1984)

Janet Jackson …………. Cleo Hewitt (1984-1985)

Page Hannah …………… Kate Riley (1985-1986)

Olivia Barash …………. Maxie (1986-1987)

Michael Cerveris ………. Ian Ware (1986-1987)

Eric Pierpoint ………… Jack (1986-1987)

Carrie Hamilton ……….. Reggie Higgins (1986-1987)

Elisa Heinsohn ………… Jillian Beckett (1986-1987)

P.R. Paul …………….. Montgomery MacNeil (1982)