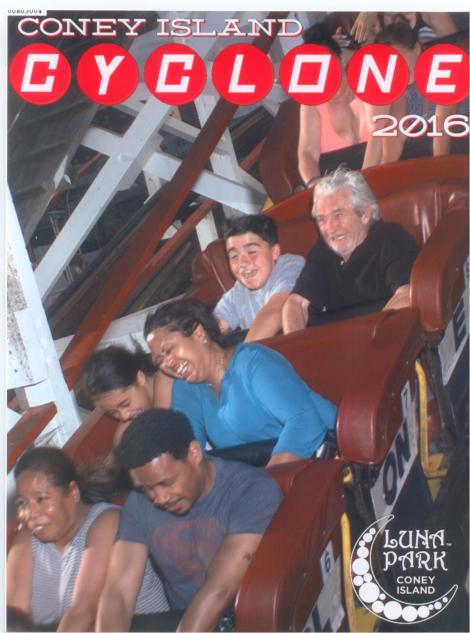

Jake and Dad

In senior year (fall, 1958) at Mamaroneck High School in Mamaroneck, NY, we presented the 1939 play Arsenic and Old Lace by Joseph Kesselring. I was lucky enough to be cast as Mortimer Brewster, the role played by Cary Grant in the 1944 movie directed by Frank Capra, after it had run on Broadway from 1941 to 1944. (I recall learning at some point that the play, about Mortimer discovering that his two beloved maiden aunts are homicidal maniacs, was originally called Bodies in the Cellar.) Anyway, I just want to tell you about what happened during our dress rehearsal…

We were rehearsing in the full set with costumes on, going through the entire play non-stop [or at least, that was the intention] while the lights were being adjusted and so on. Our director was out in the audience — Miss Schmidt, I believe — and I was onstage with the two aunts when my fiancée, Elaine Harper, came through the front door. The dialogue was supposed to go this way:

Elaine: Mortimer!

Mortimer: Elaine!

[They rush to each other and embrace.]

It sounds simple, eh? Well, the lovely girl playing Elaine arrived at the door, right on time, stepped into the living room and saw me.

It sounds simple, eh? Well, the lovely girl playing Elaine arrived at the door, right on time, stepped into the living room and saw me.

Elaine held out her arms toward me and cried: “Elaine!”

I stared back at her. After a few beats, I replied: “Mortimer?”

We all laughed so hard that the dress rehearsal stopped in its tracks. It took at least ten minutes to get back into it without cracking up again.

I have no idea how I might have reacted if this had been a genuine performance in front of a packed auditorium in the high school. But such surprises are part of the joy of acting. They give you a jolt of new energy. They put you into a state of sudden, instant aliveness. And such surprises are not at all “mistakes,” not while you’re on stage, because there’s no choice other than to react in some real, honest way — to deal with the surprise, to “go with” whatever happens, in the moment. And hopefully to deal with it the way we might do so in life itself.

Maybe I would have said to her, “Well, now, as far as I can recall, you are Elaine, and I — I am Mortimer!”

Or any of a hundred variations of that reply … or of some response that might have been much more clever.

Why have I never forgotten that moment? The jolt? The uncontrollable laughter that followed? I’m not sure that I know the answer, but it must have something to do with the way all those signals in my brain went on alert and scrambled around to make sense of things. All I really know is that, out of so many other moments involving Arsenic and Old Lace that I’ve long forgotten, that one has stuck with me.

Pulled this one from Facebook, courtesy of classmate Barrie Proctor.

Found myself in the third row from the top…

Third from the left…

The guy with his eyes closed…

Oh, well …

I miss them all!

Here’s one of my favorite photographs — a picture of my Mom and Dad (Suzette Schwiers and Bill Whittemore) in 1940 before they married that December. For me it’s an eerie sight because I am watching a moment that will lead, with other moments, to my birth on 3 November 1941, a month before Pearl Harbor. They were courting each other, yes? Elsewhere on this blog you’ll see a PARADE story about life with my mom on the home front while Dad was off to war. Here they are, on the brink:

They're in the backyard patio of my paternal grandparents' house on Virginia Place in Larchmont, New York.

My dad had grown up in the Manor section of Larchmont in a house with two other families, each with a child. One of the kids was Dad’s first cousin Claire Wemlinger, who would go on to become the great film actress and movie star Claire Trevor, known above all for her work in Stagecoach and Key Largo.

Claire died at age ninety in 2000. She was a sweetheart of a gal, full of warmth and spunk as well as talent. Her birthday was March 8th and I plan to post up a blog with a little personal stuff about her on that date coming up.

And here’s another photo…

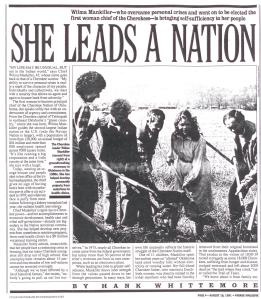

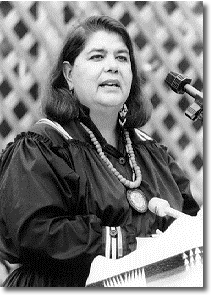

Wilma Mankiller, the first woman to be elected chief of a major American Indian tribe, who led the Cherokee Nation from 1985 to 1995, died of pancreatic cancer on the sixth of April at her home near Tahlequah, Oklahoma, at the age of sixty-four.

I have the fondest memories of visiting with her in August 1991, on assignment for PARADE magazine, and reprint my article here as a tribute to a wonderful person whose presence among us is now so greatly missed:

SHE LEADS A NATION

BY HANK WHITTEMORE

“MY LIFE MAY BE UNUSUAL, BUT not to the Indian world,” says Chief Wilma Mankiller, 45, whose name goes back to that of a Cherokee warnor. “My ability to survive personal crises is really a mark of the character of my people. Individually and collectively, we react with a tenacity that allows us again and again to bounce back from adversity.”

The first woman to become principal chief of the Cherokee Nation of Oklahoma, she speaks softly but with an undercurrent of urgency and commitment. From the Cherokee capital of Tahlequah in northeast Oklahoma’s “green country,” where she was born, Wilma Mankiller

The first woman to become principal chief of the Cherokee Nation of Oklahoma, she speaks softly but with an undercurrent of urgency and commitment. From the Cherokee capital of Tahlequah in northeast Oklahoma’s “green country,” where she was born, Wilma Mankiller

guides the second-largest Indian nation in the U.S. (only the Navajo Nation is larger), with a population of more than 120,000, an annual budget of $54 million and more than 800 employees spread across 7000 square miles.

“It’s like running a big corporation and a little country at the same time,” she says with a laugh.

Today, wearing an orange blouse and purple skirt in her office at the tribal headquarters, the chief gives no sign of having had a bout with myasthenia gravis after a car accident in 1979; and while her face is puffy from medication following a kidney transplant last year, she radiates health and energy.

Chief Mankiller’s rapid rise to Cherokee power – and her accomplishments in economic development, health care and tribal self-governance – already are legendary in the Native American commu nity. She has helped develop new projects from waterlines to nutrition programs, from rural health clinics to a $9 million vocational training center.

Mankiller freely admits, meanwhile, that her people face a continuing crisis in housing, that too many Cherokee youngsters still drop out of high school, that unemployment remains about 15 per cent and that decades of low self-esteem cannot be reversed overnight.

“Although we’ve been affected by a lot of historical factors,” she insists, “nobody’s going to pull us out but ourselves.” In 1975, nearly all Cherokee income came from the federal government, but today more than 50 percent of the tribe’s revenues are from its own enterprises, such as an electronics plant.

While leading her tribe to greater self-reliance, Mankiller draws inner strength from the values passed down to her through generations. In many ways, her own life uncannily reflects the historic struggle of the Cherokee Nation itself.

One of eleven children, Mankiller spent her earliest years on “allotted” Oklahoma land amid woodsy hills without electricity or running water. Her full-blood Cherokee father, who married a Dutch-Irish woman, was directly related to the tribal members who had been forcibly removed from their original homeland in the southeastern Appalachian states.

That exodus in the winter of 1838-39 turned to tragedy as some 18,000 Cherokees, suffering from hunger and disease, trudged westward and left about 4000 dead on “the trail where they cried,” later called the Trail of Tears.

“We knew about it from family stories,” Mankiller says, recalling how one of her aunts had a cooking utensil from ancestors on the trail. “Later we learned how our people had left behind their homes and farms, their political and social systems, everything they had known, and how the survivors had come here in disarray — but how, despite all that, they

had begun almost immediately to rebuild.”

When Mankiller was 12, in 1957, her family was again relocated — in this case, by a federal program designed to “urbanize” rural Indians. Sent from the Oklahoma countryside to a poverty-stricken, high-crime neighborhood in San Francisco, they were jammed into “a very rugged” housing project. Like their ancestors, they were forced to start over.

“My father refused to believe that he had to leave behind his tribal culture to make it in the larger society,” Mankiller recalls, “so he retained a strong sense of identity. Our family arguments were never personal but about some social or political idea. That stimulating atmosphere, of reading and debating, set the framework for me.”

During the l960s, Wilma Mankiller got married and had two children. She also studied sociology at San Francisco State University. In 1969, when members of the American Indian Movement took over the former prison at Alcatraz to protest the U.S. government’s treatment of Native Americans, she experienced an awakening that, she says, ultimately

changed the course of her life.

“I’d never heard anyone actually tell the world that we needed somebody to pay attention to our treaty rights,” she explains. “That our people had given up an entire continent, and many lives, in return for basic services like health care and education, but nobody was honoring those agreements. For the first time, people were saying things I felt but

“I’d never heard anyone actually tell the world that we needed somebody to pay attention to our treaty rights,” she explains. “That our people had given up an entire continent, and many lives, in return for basic services like health care and education, but nobody was honoring those agreements. For the first time, people were saying things I felt but

hadn’t known how to articulate. It was very liberating.”

So, in the 1970s, Wilma Mankiller began doing volunteer work among Native Americans in the Bay Area. Learning about tribal governance and its history compelled her to take a fresh look at the Cherokee experience; and what she saw, in terms of broken promises and despair, made her deeply angry.

After the Trail of Tears in 1839, rebuilding by the tribe in Oklahoma proceeded with the creation of a government, courts, newspapers and schools. But this “golden era” ended with the Civil War, followed by the western land rush by settlers who devoured Cherokee holdings. In 1907, Washington gave all remaining Indian territory to the state of Oklahoma

and abolished the Cherokees’ right to self-government. “We fell into a long decline,” Mankiller says, “until, by the 1960s, we had come to feel there was something wrong with being an Indian.”

Not until 1975 did U.S. legislation grant the Cherokees self-determination. As rebuilding began yet again, Mankiller’s own transformation was progressing as well. In 1977, after being divorced, she returned with her children to Oklahoma.

Working in community development, Mankiller saw that the tribe’s need for adequate housing, employment, educa tion and health care was staggering. She helped to procure grants and initiate services; but, she says, she was still angry and bitter over conditions — not yet the calm, introspective woman capable of leading the Cherokee Nation.

Then, in the fall of 1979. an oncoming car collided with her Station wagon. She regained consciousness in the hospital, with her face crushed, ribs broken and legs shattered.

Months of recovery included a series of operations and plastic surgery on her face. Then she developed myasthenia gravis, which sent her nerves out of control. Surgery on her thymus was followed by steroid therapy. Yet, in December 1980 — just over a year after the accident — she went back to work.

In a profound way, however, Wilma Mankiller was a different person. “It was a life-changing experience,” she says. To sustain herself through recovery, she explains, she drew upon precepts that the Cherokee elders had taught her:

• “Have a good mind. No matter what situation you’re in, find something good about it, rather than the negative things. And in dealing with other human beings, find the good in them as well.”

• “We are all interdependent. Do things for others — tribe, family, community — rather than just for yourself.”

• “Look forward. Turn what has been done into a better path. If you’re a leader, think about the impact of your decisions on seven generations into the future.”

The same woman who had been im mobilized became a bundle of energy relentlessly focused on getting things done. After she helped obtain a grant enabling rural Cherokees to build their own 26- mile waterline, male leaders took notice. By 1983, she was being asked to run for election as deputy chief. Two years after that victory, when Chief Ross Swimmer was named head of the Bureau of Indian Affairs, Mankiller became the principal chief.

Then, in the 1987 election, she ran for a full four-year term, becoming the first woman elected as Cherokee chief.

“Wilma is a breath of fresh air in In dian leadership,” says Peterson Zah, 58, president of the Navajo Nation and a friend. “She is a visionary who is very aggressive about achieving the goals she has in mind for her people. She truly cares about others.”

As chief, Mankiller works 14-hour days filled with meetings in Tahlequah and frequent twin-engine flights to the state capital in Oklahoma City; and she is often in Washington, D.C., lobbying Congress. Her second husband, Charlie Soap, a full-blood Cherokee, keeps up a similar pace developing community programs. “We can’t wait until the end of the day,” Mankiller says, “to tell each other what went on.”

They had long talks before Wilma de cided to run for a second full term in June. Her recent kidney transplant was successful (the donor was her oldest brother, Donald Mankiller), but she has yearned to do more “hands on” work in rural communities; and there have been enticing offers to teach.

“Committing to another four years was a big decision,” she says. “Basically it came down to the fact that there are so many programs in place that have been started but aren’t yet finished.”

On June 15 — with 83 percent of the vote — Wilma Mankiller was re-elected for four years, beginning Aug. 14.

As she starts her second term, Mankiller sees clearly the depth of problems of her own people, but her vision also includes a national agenda for all Native Americans,whose emerging leadership has heartened her.

One afternoon recently, Mankiller joined other tnbal chiefs in Okiahoma City in a meeting with the governor’s staff about a plan to tax Indian-owned stores. During a long discussion, Chief Mankiller kept silent; but when she finally spoke up, it was in a way typical of her strong yet quiet leadership. “I suggest you look at existing tribal contributions to the state,” she said in a soft voice, “and decide not to impose any new taxes on us. This is an opportunity for the state to begin a new day, an era of peace and friendship, with the tribes. Deciding against a tax would send a clear signal to the Indian population with long-term, positive impact.”

Although the decision was left hanging and has yet to be resolved, in a single stroke Mankiller had elevated the meeting’s theme. Then she was off to board a small airplane back to Tahlequah.

Flying over the lush green country side where her people have lived for a century and a half, she could see the Cherokee Nation spread beneath her.

Flying over the lush green country side where her people have lived for a century and a half, she could see the Cherokee Nation spread beneath her.

“We can look back over the 500 years since Columbus stumbled onto this continent and see utter devastation among our people,” she says. “But as we approach the 21st century, we are very hopeful. Despite everything, we survive in 1991 as a culturally distinct group. Our tribal institutions are strong. And I think we can be confident that, 500 years from now, someone like Wilma Mankilier will say that our languages and ceremonies from time immemorial still survive.”

As her plane descended, some children paused briefly to glance upward before returning to their lives and to the “new day” that Wilma Mankiller was trying to create for them.

The chief was home.

JIM CRAIG:

One Young Man Americans Would Like to See Win New Glory

Thirty years ago I interviewed Jim Craig in Boston some months after he had led the U.S. hockey team that beat the supposedly unbeatable Soviet Union in the 1980 Olympics. In those days Craig was a national hero; today he’s a national legend. And he’s been up there in Vancouver rooting with the rest of us for Team USA.

Re-reading my article, I marvel at the wisdom Jim Craig possessed even then. He’s the real deal! Here’s the full text of what I wrote:

PARADE

September 21, 1980

By Hank Whittemore

No one who saw it will ever forget. When the U.S. Olympic hockey team did the impossible in Lake Placid and skated off with the gold medal, it was a victory America needed.

A handful of youngsters were the nation’s gladiators-on-ice, briefly reducing the entire- world political situation to the resounding chants of U.S.A.! U.S.A.!”

In the midst of it all, goalie Jim Craig stood apart from his exuberant teammates, searching the stands and asking aloud, “Where’s my father?” As he counted the rows of seats in a vain search for his dad, the millions watching had sudden lumps in their throats, tears in their eyes. By instinctively reaching out for his family, this one young man had tapped the deepest impulses in America’s heart.

[NOTE: Jim has a great personal website]

Now Jim Craig is a professional hockey player, entering his first season with the Boston Bruins, but no matter what happens he will always be more than that. Wherever he goes (and he’s been “going” constantly since last winter), he is a national hero and a symbol of the best the country has to offer. Always, there is applause; and nobody knows the meaning of it better than he does:

“People are expressing their happiness about themselves. Through me, they see the country and clap for themselves. I’m a vehicle, that’s all I am, and it’s great. I just want to be used in a positive way.”

Craig is not the matinee-idol type like Bruce Jenner to name another Olympic champion who stirred the nation’s emotions. Rather, he is the product of the sprawling, Irish-Catholic neighborhoods of Boston. He has the unshaven, unpretentious, rugged look of the working class, and there is a feeling that he would be far more at home in a local tavern than signing contracts for commercials up in the plush offices of his agent.

From a blue-collar section of North Easton, Mass., Craig is full of restless energy and strength. This past summer he could be spotted easily as he rode through Boston in his jeep, hopping out on Federal Street wearing a T-shirt, a bathing suit and a pair of old sneakers without socks.

At 23, he retains his love for family, friendship and basic values, but by now he also admits that he is “smarter” and “not so naive” and “a little more cynical” about the world. The Great American Media machine has created one of its overnight celebrities and woe to him if he falters.

So it is no wonder that Jimmy Craig, a carefree spirit if there ever was one, has developed a tension ulcer. It is no wonder that he still wants to be with his father, three brothers, four sisters and Huey, the dog. It is no wonder that he is so thrilled to be playing for the Bruins this season, in his own back yard. The applause of strangers must be balanced by the familiarity of home and strength of his roots. Otherwise, the pressure of it all would flatten him faster than a speeding hockey puck.

“The biggest thing I know,” he says, “is that they want to make a hero, but they also want to knock you off that pedestal as quickly as they put you up there. And that’s why I don’t consider myself a hero or anything like that. The Olympics was the highest moment of my life and no matter what I do, I’ll never be able to touch it. So now I just take one day at a time and do what I think is right. See, I know everything that goes on in my own head, and as long as I can live with myself, I know I’m doing okay.”

The new Jim Craig might be likened to a kitten venturing out into full cathood. On the one hand he is totally relaxed and loose, just being himself; and on the other, he is poised, always on the alert for danger. Very much like the goalie that he is, he crouches, ever- watchful, waiting for the action as it speeds inevitably his way.

“I’m going to survive.” he says. “I’m a survivor. I’m going to do a good job at whatever I do, because I feel obligated to myself. My biggest goal now is being a professional hockey player and doing well for the Bruins. I’ll be a big disappointment to myself if I don’t play well this season.

“Fortunately I simplify everything as much as possible. I don’t put any more pressure on me than I have to. If I walked around trying to act a certain way all the time, I’d be a basket case. You can fool everyone in the world, but not yourself.”

After Lake Placid, Craig was catapulted into a whirlwind: lunch at the White House, appearances on television, parades, speeches, airplane crowds and more crowds. In Chicago, he walked into his hotel room and found a nude woman lying in his bed.

“Please leave,” he told her, having no need for such favors, and besides, the cat had reared up its back: “You never know, it could have been a setup.”

Craig also joined the Atlanta Flames hockey team and tried to help save their franchise. Under tremendous stress he played four games, winning one, losing one and tying two. Despite his numerous promotional appearances for the Flames, and a burst of new life at the box office, the team was sold to Calgary and Craig wound up with his tension ulcer. In June, he was traded to the Bruins and went home.

“It couldn’t be better,” he says with a look of wonder in his watery blue eyes. “You know that phrase, ‘You were made to be there’? Well, I’m made to be here.” As if life were a storybook, he will be playing with the team he rooted for as a boy; and his boyhood idol, Gerry Cheevers, retired as goaltender and became the Bruin coach.

“Unbelievable.” Craig says with a smile.

Until the summer, Craig still lived in the house in Easton, where he had grown up as the sixth of Donald and Margaret Craig’s eight children. Now he has his own apartment in Boston, not far away; but the roots of his Irish- Catholic background are still his main source of nourishment.

“I love my family,” he says, and it still amazes him that people enjoy hearing him express that simple, strong emotion, as if it were unusual.

“My father never made more than about $13,000 a year when I was growing up, but I consider myself fortunate. Dad was a food director at Dean Junior College up in Franklin for 28 years. He was like a father to those kids, too. He worked seven days a week and really enjoyed it.

“The amazing part, though, was that he’d come home after a long day and always have time for us. He wouldn’t grouch and say, ‘Leave me alone.’ Never. Instead, he’d go out and hit balls to us and so forth,

“I feel very lucky that I got to thank my old man before it was too late. These days there are so many kids who want to give their old man a big hug and a kiss, but they can’t. Fathers think that if they send ’em to the best prep schools or give ‘em the car or money, they’ve done a good job. ‘So why doesn’t my son love me?’ they ask.

“Why not? Because that’s not what the kid is looking for. And if he doesn’t get it, he’ll miss it when he’s older. In my opinion, if a kid doesn’t have a relationship with his father before he’s 16, he won’t have one later on. The giving and taking has to start before that age or it never will. By then, there are too many gaps to fill.”

Craig’s mother, who died of bone cancer in 1977, was an even greater influence on him. “It was as if she was a big bear and we were all her cubs.” He recalls. “She was a great, great lady, and all I have is fond memories. My parents played typical roles – Dad going out to work, Mom taking care of us kids and giving the discipline. When she died, my father had to switch roles suddenly and do a little bit of everything.”

When Jim Craig was real small, he would go down to the frozen ponds on a narrow section filled with trees, and while the older boys played hockey, he would skate on a narrow section filled with trees. “It was like an obstacle course,” he says. “There was just enough ice around the trees to skate in-between.”

From then on, the obstacle courses grew tougher, but Craig seemed to glide through them all with hard work, strength, instinct and grand success. He played goalie in high school and his team racked up 53 wins, three losses and a tie. In his sophomore year at Boston University, the Flames drafted him, meaning that they would “own” his services after college.

Meanwhile, he led the 1978 B.U. team that won the National Collegiate title. After graduation, he postponed the professional career and went off to Moscow with the U. S. 1979 national team for the World Games.

“I hated Moscow,” he says. “It was just awful. You get off the plane and they have guys with machine guns putting you on a bus. They had KGB agents following us everywhere we went. A very scary experience. On the ride home, we sang ‘God Bless America.’”

Then came the Olympic triumph at Lake Placid, followed by the whirlwind, the Flames and the call back to Boston. Craig signed a contract with Coca Cola (he received $35,000 for doing a one-shot TV commercial), committing himself to make 10 appearances around the country. Under the guidance of his agent, Bob Murray, he has accepted dozens of invitations to appear at charity events, and to give speeches, in nearly every state.

“We also turn down a lot of things,” Craig says. “Everybody wants a piece of me, but I want to do only quality things. I feel a moral obligation to certain friends and charities, but I’m going slow. I try to spend three days a week with my family and keep my feet on the ground.

“I date girls here and there, but I don’t want to be tied down yet. I just want to go out and have fun, with no strings attached. No commitments. Just friends.”

Once again, it is the instinct of the cat who is suddenly out in the world, feeling his way along and trying to learn while not getting trapped. In his quest to be an award-winning .pro hockey player, Craig has vowed to re main unmarried for at least five more years.

In this new, high-pressured world he has entered, Craig is still speeding through the obstacle course: “People tell me, ‘Oh, Jimmy, you gotta be careful. They’re all using you.’ Hey, I’m just being me. And if anybody’s using me, well, I’m using them too. What I’m trying to do is just learn from people.

“I’m not an intellectual, but I have lots of common sense, I can get fooled once, but I won’t make the same mistake again. If somebody is my friend, he’s my friend. If he’s not, he’s not. And I’ll tell him right up front.

“But do you know how lucky I am? To be able to travel and meet so many people? Their character comes out without them even knowing it. You can see the character in a person, or the lack of it, right away. And when I meet a guy with experience. I’ll sit there and just listen.”

That is Craig’s way of educating himself, not through books but from life itself. Long before he was sharing platforms with governors and movie stars, he was studying people in all walks of life. He did so when he moved furniture, landscaped gardens and painted houses. He learned from the well-to-do when he caddied at Thorny Lea Golf Club (where he now has a free membership), and from dock workers when he packed groceries in Fernandes Supermarket.

Over the summer, however, Jim Craig went to California by himself, with no one. For nine days, he stayed in a house without a telephone. Slowly, gradually, he began “getting mentally ready” for the Bruins.

From now on, Boston will claim him as its own; but a sure bet is that America will not forget him and the other boys of winter for a long, long time.

—

FAME 2009 the movie failed to live up to the original FAME of 1980, and the TV show that followed, but I figure it’s time to reprint my PARADE article in 1982 on the real-life “Fame School” — the High School of Performing Arts in New York City.

FAME – The Real Story

PARADE – August 22, 1982

By Hank Whittemore

“I want to live forever . . . Baby, remember my name!”

Those words are from the theme song of the movie Fame. They sum up Hollywood’s version of what drives the students at the prestigious School of Performing Arts in New York City, which inspired the film and the TV series that followed it. In both, talented young actors, singers. dancers and musicians are portrayed as having little else on their minds except seeing their names in lights.

In reality, though they may arrive as freshmen with stars in their eyes and “remember my name” in their ears, that ego trip ends when they walk through the door. The message turns out to be entirely different. The six hundred students at “P.A.” – as they affectionately call their unique public high school – regard celebrity as an elusive, fleeting and even unworthy goal.

Their talk spills over with words like achievement, commitment, integrity, quality, respect, work. One word that almost never comes up is fame.

“The TV series doesn’t truthfully portray what kind of people we are,” says Oliver Barreiro, a junior in the drama department. “They make it seem as if everything is a playground. with singing and dancing on top of cars.”

“They don’t show the commitment needed to work in this school,” adds Caren Messing, another acting student. “They’re very result-oriented. All you see are these musical numbers, with kids performing all the time. But we deal with the process and the practice.”

The film did capture the highly competitive audition process required for admission – out of about 4500 annual applicants, only 200 new students are accepted – and the school’s balanced racial mix. “This is a school where black kids, white kids, Puerto Rican kids, yellow kids and all the others come together to be liberated,” says Jerry Eskow, chairman of the drama department. “In a real sense, they are all breaking out of their individual

ghettos.”

One of the graduates this year is Erica Gimpel, who took time off to play the leading role of Coco Hernandez in the Fame TV series. In a press release, MGM Television speaks of Coco’s “consuming hunger for success.” She “knows she’s bound for stardom and fame,” it adds. “It’s just a matter of when it will happen. Her choice is tomorrow … or sooner!”

The real Miss Gimpel is a serious acting student – not a dancer like Coco – and she could hardly wait to get back from Hollywood to continue her work at P.A. There she is treated as an equal, not as a celebrity. “Erica came back to school to find the reality,” Eskow says. He adds that, like her classmates who regularly watch her on Fame, “she understands the difference and feels just as strongly about work as they do.”

For Gene Anthony Ray, who played the role of Leroy Jobnson – a streetwise, resentful black dancer – in both movie and series, the difference between Hollywood and reality is perhaps more ironic. Ray had been a Performing Arts student, but he left the school without completing its program. In the screen version, however, Leroy is kept on and even treated as a special case.

“Now, that’s really unrealistic,” says Corinth Booker, a young black student and, like Leroy, a dancer. “And on the series, nobody wants to get on Leroy’s bad side because he’s so talented. Here, there’s just no kind of favoritism like that. Leroy gets away with being very stubborn and selfish, and he argues with teachers – like, ‘Are you telling me what I should do?’ That’s not the way it is.”

As head of the P.A. dance department, Lydia Joel resembles a strict but caring aunt. Her lecture to freshman dancers comes right to the point “This is an absolutely undemocratic situation you face. You have no rights here. Your only right is to come to class and be wonderful. You can’t protest, you can’t be absent, you can only work. If you are aspiring to work on the professional level, there is only quality, quality, quality. And we will help you be wonderful.”

“Dancing is an extraordinary human endeavor,” Joel tells her students. “We can try to find flexible bodies, vitality, response to instruction and the potential for achievement, but what we really can’t judge is your motivation. It’s like a little flame that burns inside of you. And no matter how much you want to be a big star, it won’t work if that fire doesn’t burn strongly enough to give you the patience and dedication you need. You must give your entire self in an act of faith. If you have any sort of resentment or lack of clarity, you will find heartbreak. But if you manage to live through four years of this

demand upon your inner self, your life will be literally changed.”

The students say that Hollywood’s depiction of competitiveness among them is unrealistic. “It seems like everyone is scratching their eyes out to beat each other out,” Oliver Barreiro says, “but that is just the opposite of how it works here. We don’t talk about each other behind our backs. We work together, all striving for the same thing.”

In a city loaded with crime, drugs and other problems involving teenagers, P.A. students insist that drug usage is far less here than at other high schools. “They have real respect for their bodies,” says Fred Wile, P.A.’s guidance counselor. “Just as you can’t be twenty pounds overweight and function as a dancer, you certainly can’t play Beethoven while you’re stoned on drugs.”

Long before Fame the movie brought Performing Arts into the national limelight, the school was known among professionals as the alma mater of such stars as Al Pacino, Lisa Minnelli, Ben Vereen, Melissa Manchester and the late Freddie Prinze. And to most of its illustrious graduates, the school is something very special. “I tell my freshmen students to go out and interview an actor or director,” Jerry Eskow says, “to find out what they feel is important. And even the biggest stars will talk to a kid from Performing Arts.”

Dustin Hoffman, Eskow recalls, was approached one time by a fourteen-year-old girl from the drama department. “Could you give me an interview?” she asked.

“No time,” Hoffman said.

“I’m from the School of Performing Arts.”

“Oh! Well, listen,” Hoffman replied, “I can’t do it now, but why don’t you come to my home tomorrow morning?”

When she arrived, Hoffman was still asleep, but he roused himself for the interview. The girl couldn’t get her tape recorder to work and started to cry. Hoffman helped her with the machine and even conducted the first half of the interview by asking himself questions until she overcame her shyness.

Another student approached George C. Scott at a time when the actor was refusing to talk to the press. As Scott emerged from a lobby in Lincoln Center, the young man tried to get his attention.

“What the hell do you want?” Scott roared in his familiar gruff voice.

“I’m from the School of Performing Arts.”

“Come on,” Scott barked, grabbing the student by the arm and marching him across the street to a drugstore. “Sit down,” he said, ordered coffee for them both and launched into a forty-minute interview as if it were the most important thing in the world.

Which, of course, it often is. The youngsters are being asked to look deep within themselves and come up by age seventeen with answers to the questions: “Do I have what it takes? Should I make this my whole life?”

“Talent is all around us,” Eskow says, “but the trick is to identify it and then help the students to see themselves as talented entities rather than as street kids.”

“Most schools see a student as an empty vessel to fill with knowledge,” he explains. “We believe that these kids are the reverse. You go to a medical school and come out a doctor. Here, the actor or dancer or musician already exists, and our job is to peel away the layers preventing that professional from emerging.”

At 6 a.m. on weekdays, dance student Corinth Booker wakes up in Harlem, does his chores, takes his little sister to a babysitter’s apartment and then rides the crowded subway down to the very different world of Performing Arts. He attends his classes, goes through muscle-numbing practice sessions, takes more dance classes on the side and works as a busboy three nights a week. He has his chance, yet he knows time is already running out.

“They want these young dancers out there,” says student Terri Hall. “It’s like, if you’re twenty, you’re old! I mean, at sixteen, I’m halfway over. I’m really so unsure about what want now. If I went to college, I wouldn’t major in dance because the level isn’t high enough. Should I stay in New York when I graduate? On the Fame series, you never see any of the characters going through these changes.”

Henry Rinehart, also sixteen, says he has lost his adolescence by having had to make his own way in the city while studying acting at P.A. His parents are separated, so he lives at another student’s apartment and copes on his own. “I’m supposed to be a teenager growing up.” he reflects, “but I look at myself and find that I’ve already done it.”

The reality, Henry says, is learning about failure: “They tell us, ‘If you’re going to fail, do it here and go all the way. Fail big!’ Because you learn so much from having to pick yourself up and go on. In deciding whether to continue as performers, we’re really experiencing how to face life.”

Nina LoMonaco, seventeen, is another part of the reality, practicing her French horn on the staircase, blowing it so loudly that the paint starts chipping and falling down all around her. While other young people are off having a good time, she studies and practices hour after hour. She says she often wonders: “My God, am I making the biggest mistake of my life? What am I doing this for?”

Should Nina skip regular college and try to become one of the best musicians in the country? “I can understand people getting discouraged,” she says, “but that’s fine because it’ll mean less competition for me. I’m going to reach as high as I can, and if I don’t make it, that’s my problem. But I have to take this chance. Now.”

Is the punishing life of a dancer the only way Corinth Booker can break out of Harlem and the urban jungle? How will Henry Rinehart know, really, if he has what it takes to be a professional actor? Does Terri Hall honestly want the life of a dancer to the exclusion of so much else?

In the real world, these youngsters are at the edge of adolescence, looking out at an unclear future. Yet they have to make decisions about leaping into it. They’re seeking an answer – some sort of message that will make them decide one way or another.

For Lydia Joel, the answer comes every day. As we sit in the tiny office from which she runs the dance department, the pounding of a practice piano underscores the sound of dancers practicing in a studio two floors above. In another room, a student orchestra plays. Down the hall, some acting students rehearse a scene from Euripides.

“These kids are beautiful in the right sense of the word,” Lydia Joel says. “The sounds of this school are the sounds of involvement.”

Then she picks up a postcard from a former dance student: “I would like to thank you for recommending me. I did very well at the audition and in made it to the last 15 out of 300 girls. But nothing came of it. Well, maybe next time. I’m not going to give up. I love it too much.”

She puts down the postcard. She sighs. “One very beautiful girl who was doing quite well came to me last year and told me she’d decided to become a nurse instead of a dancer. The flame inside her burned toward nursing. But here,” she points to the postcard, “the flame is toward the dance as a way of life. That’s how it burns.”

Flame – not fame – is the message.

///////////

Fame TV Show Cast:

Debbie Allen .…………. Lydia Grant

Gene Anthony Ray ………. Leroy Johnson

Carlo Imperato ………… Danny Amatullo

Albert Hague ………….. Mr. Benjamin Shorofsky

Ann Nelson ……………. Mrs. Gertrude Berg

Carol Mayo Jenkins …….. Elizabeth Sherwood (1982-1986)

Billy Hufsey ………….. Christopher Donlon (1983-1987)

Valerie Landsburg ……… Doris Rene Schwartz (1982-1985)

Bronwyn Thomas ………… Michelle (1982-1985)

Cynthia Gibb ………….. Holly Laird (1983-1986)

Jesse Borrego …………. Jesse V. Valesquez (1984-1987)

Nia Peeples …………… Nicole Chapman (1984-1987)

Lee Curreri …………… Bruno Martelli (1982-1984)

Morgan Stevens ………… David Reardon (1982-1984)

Ken Swofford ………….. Quentin Morloch (1983-1985)

Loretta Chandler ………. Dusty Tyler (1985-1987)

Graham Jarvis …………. Mr. Bob Dyrenforth (1985-1987)

Dick Miller …………… Mr. Lou Mackie (1985-1987)

Lori Singer …………… Julie Miller (1982-1983)

Erica Gimpel .………Coco Hernandez (1982-1983)

Dave Shelley ………….. Caruso (1983-1984)

Janet Jackson …………. Cleo Hewitt (1984-1985)

Page Hannah …………… Kate Riley (1985-1986)

Olivia Barash …………. Maxie (1986-1987)

Michael Cerveris ………. Ian Ware (1986-1987)

Eric Pierpoint ………… Jack (1986-1987)

Carrie Hamilton ……….. Reggie Higgins (1986-1987)

Elisa Heinsohn ………… Jillian Beckett (1986-1987)

P.R. Paul …………….. Montgomery MacNeil (1982)

Here is one of my all-time favorites among the articles I wrote for PARADE from the mid-1970’s until the mid-1990’s. There’s no need for me to explain up front; I think it speaks for itself:

Two brothers renew a family bond and make a discovery

A POCKETFUL OF DREAMS

PARADE – September 15, 1985

My brother Jim and I have seen ourselves through many good and bad times by going out to the alleys. When one of us feels high or low, the other might say, “Let’s go rolling.” Pretty soon we’re bowling as if our lives depended on getting strikes or spares.

To explain, first I should mention Grosso’s Alleys. This was a worn-out, ancient bowling establishment in my hometown of Larchmont. N.Y. I used to go there with my grade-school friends on weekends. Jim was still too young to bowl, but he knew that I went there often. He knew I went rolling even in the summertime, when other kids were outside at the beach or playing ball. He figured there must be something special and even magical about the place.

Grosso’s Alleys was up a flight of old wooden stairs, above a row of stores. To me, it was a second home. I thought of Mr. and Mrs. Grosso as another set of grandparents. It was still the ‘50s, and in those days the alleys had no computers or pin-setting machines, so we had to keep score and have the pins set by hand. When my friends and I bowled, we acted as pin boys for each other.

We became acquainted there with the men who made a living by setting pins. They earned a quarter a game. When all twelve alleys were filled with league bowlers, Mr. and Mrs. Grosso often allowed us kids to work as pin-setters too. That was my first real job. It felt good to be sweating down in the alley pits with the grown men and to be making my own money – which I usually spent on more bowling.

In the fifth grade, I rolled a 207, thanks to an older boy who taught me how to throw a pretty fair hook. One Saturday morning, my Dad and I won a father-son tournament. It gave us a new feeling of closeness. We brought home a trophy in the form of a bowling pin crudely painted red, blue and yellow to resemble a doll.

My brother took that weird-looking trophy into his hands. He stared at it with an expression of awe. I knew right then that before long he, too, would be rolling.

Now, there's a nice hook for you -- spinning its way off the edge of the gutter before heading for the pocket!

By the time I was in high school. Grosso’s Alleys was designated a fire hazard and closed down. Meanwhile, a new, modern bowling establishment was built nearby. Lots of us would go there to roll and play the pinball machines and hang around with the girls. In fact, it was at the new alleys that I met my steady girlfriend, whom I eventually married.

I was on the varsity bowling team. The five of us wore glossy orange shirts with our school initials printed in black. Each week, we went to a new set of alleys to roll against a team from a different high school. There were no cheerleaders, no spectators. It definitely wasn’t a glamour sport.

At the same time, off somewhere by himself, Jim was rolling and perfecting his game. He was catching up with me. When I went away to college, he wrote to say that he’d bowled a 253. That, I had to admit, was a family record.

When I was back in town as a married man with a newspaper job, occasionally Jim would call and say, “Want to go rolling tonight?” For us, bowling was a way of staying in touch. It gave us a lot of laughs. The time I flung a ball and ripped the seat of my pants up the middle, I thought he’d die.

It also gave us a chance to talk and express our visions of the future. He and his girlfriend were going to get married, Jim said, and then he and I both would have families. We would grow old together as brothers, fathers and uncles, watching our children and grandchildren share their lives and even bowl together. That was one of his dreams.

While rolling we competed, but not really against each other. What we were doing was “searching for the pocket.” We meant trying to find the exact spot to hit on the first throw, so all ten pins would go down for a strike.

We taught each other that finding the pocket is an elusive goal. If you try too hard you lose it. You have to throw the ball out toward the gutter, so it has room to curve back in. You have to let go and not be afraid and trust your natural hook. You can’t force the destiny of the ball by aiming directly into the pocket.

Even if you do find it once – getting a strike – the important thing is to do it again. And again. And again. Any triumph is only fleeting at best. It quickly recedes into the past, and you are faced with ten more pins all over. We decided that bowling, by itself, means very little. What counts is how you bring yourself to the game. What matters is not how good or bad your previous try was, but viewing each new roll as the first, last and only one.

We knew without saying it that the lonely concentration and persistence required by bowling has something to do with what’s required by life.

And, in fact, life took over.

When the Vietnam War started building up, my brother joined the Navy. He went to the Philippine Islands and was stationed on the base at Subic Bay. We wrote back and forth all the time, and the tone of his letters grew increasingly bitter.

He was always under the threat of being shipped over to “Nam,” but what made him angry was the thought that he’d been abandoned by people at home. He imagined that all of his friends in the States were growing their hair long, using drugs and protesting against the war. He was several thousand miles away, trapped in his uniform. He felt misunderstood and cut off.

My brother's not in this picture, but I'm sure he sat at one of those tables with a very similar bunch of guys ...

Jim wasn’t alone in that feeling. Just about every week, one of the guys in his barracks would receive a painful “Dear John” letter from a girlfriend, telling of her decision to break off the romance. In the minds of the guys in the barracks, all the girls back home were wearing beads and becoming hippies; and. in their worst midnight fantasies, all were sporting T-shirts either denouncing the military or advertising free love.

My brother tried to cheer up his buddies by holding a ‘Dear John” contest. The winner would be the guy who received a letter using the most original excuse for dumping him: “Dear John. I’ll al ways love you, but I’ve become a different person, and you wouldn’t know me anymore, so…”

The standings in that contest kept fluctuating with the incoming tides of mail. No one, however, could top the experience of the guy who received a copy of his hometown newspaper and discovered a photograph of his fiancée in a bridal gown, taken after her wedding to someone else.

Eventually Jim, too, got a “Dear John” letter. It was from that girl he had planned to marry. He’d felt it was coming. Now he went into a rage and took action – for himself and for his Navy pals.

What he did was form a bowling team. He took four volunteers from the barracks and told them, “I don’t care what it takes – we’re going to beat every team on the base!”

None of his recruits was a great roller. A few had never even bowled before. It didn’t matter. My brother channeled all his fury and pain into this bunch of fledglings. He took his nervous, skeptical players onto the alleys and drilled them in practice. He cajoled and inspired them. Once, to make them see that anything was possible, he lobbed the ball over to an adjacent alley and made a strike for another bowler. His amazed teammates roared with delight. For a while, they even forgot the girls back home.

Jim and his four colleagues entered formal competition on the base. With the concentration and persistence that bowling requires, he rolled up terrific scores. His fellow players continually surprised themselves, week after week, spurred on by a wild cheering section made up of the other guys from their barracks. In the Navy on the Philippines, bowling had been turned into a glamour sport.

Jim’s team got into the finals. In the championship match, they went up against five officers whose scoring average – not to mention rank – was much higher. It started off as a lopsided contest, but in the end my brother and his motley band of bowlers prevailed. Their barracks mates erupted onto the alley as if the World Series had just been won.

In his letter to me, Jim described the triumph and added, “Wish you’d been here.”

After returning home, Jim looked back on his experience in the Navy with mixed emotions. He had used bowling to help him and his friends survive the long period away from home, but he also found it hard to forget the feeling of having been abandoned by people in the States.

And he couldn’t really get over that “Dear John” letter he’d received from his girlfriend. He did get married, to someone else, but the marriage ended in divorce.

My brother Jim Whittemore (the handsome guy at left) became a great success in the real estate business in Westchester County -- here in an earlier stage of his career, with former partner Emmy Lou Sleeper at right

By now, we were leading very different lives. He was in real estate, I was an author. We still got together and talked a lot and shared our feelings, but we lived in separate worlds. And we didn’t bowl.

By the fall of 1982, my marriage of nearly 20 years was over. I joined my brother in the ranks of divorced men and found myself in a daze and feeling low. I couldn’t start up my life again. When Jim invited me into his home, I accepted with a shrug. He gave me a room upstairs and left me alone. He asked no questions. He watched me mope around and heard me blame myself for being a failure.

Several weeks of this went by. On a Saturday, Jim announced that we were going to a sporting goods store. When I asked why, he said nothing and drove to town. Inside the store, I followed him to the counter.

“We want to buy a couple of bowling balls,” he told the sales clerk. “With ball bags. And we need some bowling shoes.”

“This is crazy,” I told him as the balls were fitted to the size of our hands, “The last thing I want to do is bowl. I hate that stupid game.”

A few days later, we were on the alleys. This was the first time in our lives that we had our own equipment. We took our new bowling balls out of our new bowling bags and put on our new bowling shoes. We started to roll.

My younger brother, who used to look with awe at my trophy from Grosso’s Alleys, beat me soundly game after game, showing no mercy. I kicked the ball- return rack. I sent my new ball flying so hard that it slammed into the pin-setting machine. I snarled at a kid, just because he was staring at me. Through it all, Jim pretended not to notice and just kept knocking down more pins.

After that, we bowled each week with the same results – until, at some point, all my frustration seemed so useless that I finally let go and relaxed. I created a mental picture of the ball’s journey into the pocket, but otherwise I forgot my tension and simply rolled as if each new shot were the first, last and only one. Soon my game progressed, and I started catching up with him – the way, long ago, he’d caught up with me.

One day, up in his guest room, without realizing why, I began packing my bags. I walked down the stairs and announced to Jim that I would be going off on my own. He didn’t seem surprised. I thanked him for the room and explained that I’d stopped living in the past and that it was time to get on with the rest of my life.

As we stood facing each other at the front door, I knew he was thinking about those old dreams of the future and about how the future, which was here, hadn’t become exactly what either of us had envisioned. He blinked tears from his eyes.

“I guess,” he said, “were still searching for the pocket.”

“We’ll never stop,” I said. “And we’ll find it, too.”

We stared at each other until, slowly, he forced a smile.

“Listen,” my brother said as I turned to go, “if you don’t mind, I’ll keep your ball right here in my closet, and whenever you stop by, if we feel in the mood, we’ll – ”

“Of course,” I said.

We hugged.

Of course, Jim – we’ll go rolling.

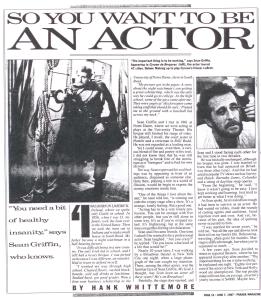

When the rave reviews appeared earlier this year for Conor McPherson’s The Seafarer at Seattle Repertory Theater, I was not surprised to read that among the actors on stage “the real show-stealer, stumbling about, spitting out curses in his charming brogue,” was my old friend Sean Griffin, whom I had met for the first time during our college days at the University of Notre Dame.

To put it simply, he is one of the best actors of his generation. The man is an actor’s actor, a guy who loves to work, and he’s continued to work for nearly four decades. Sean has appeared on Broadway and on the most prestigious regional stages across the country, in countless roles, and he’s played dozens of parts on film and television, not to mention commercials and voice-overs.

Back in the 1980’s I had the good fortune to be able to write an article about Sean that appeared in PARADE magazine; and I’d like to share it with you here:

Back in the 1980’s I had the good fortune to be able to write an article about Sean that appeared in PARADE magazine; and I’d like to share it with you here:

SO YOU WANT TO BE AN ACTOR

By Hank Whittemore

PARADE – June 7, 1987

“I was born in Limerick, Ireland, where we spoke only Gaelic in school. In 1956, when I was thirteen, my family took the boat over to the United States. Then we took the train out to Indiana and rented a small house in South Bend. My father became a night watchman in a ball-bearing factory.

“It was difficult being in a new country. The only Irish kid in school, and I still had a heavy brogue. I was picked on because I was different, an outsider. Had to learn to defend myself.

“I worked my way through high school. Cleaned floors, washed blackboards, sold soft drinks at lunchtime. Studied hard, got good grades. Won a four-year business scholarship to the University of Notre Dame, there in South Bend.

“My picture got in the paper. A story about the night watchman’s son getting a great scholarship, which was the only way he could go to college. At the high school, some of the guys came after me. They were angry at ‘this foreigner come taking stuff that should be ours.’ Pinned me to the ground with a baseball bat across my neck.”

Sean Griffin and I met in 1961 at Notre Dame, where we were acting in plays at the University Theater. His brogue still limited his range of roles. He played, I recall, the court jester in Hamlet and a crewman in Billy Budd. He was not regarded as a leading man.

Yet I could sense, even then, a curious blend of fire and poetry in his soul. I did not know then that he was still struggling to break free of the stereotype as a “foreigner” and to find his own identity.

The way Sean expressed his real feelings was by appearing in front of an audience, disguised as someone else. Only then, playing a role in a world of illusion, would he begin to expose the stormy emotions inside him.

“One of the things I love about theater,” he once told me, “is coming out onto the empty stage after a show. It’s a strange, lonely feeling. But a good one.

“Acting has to be a very lonely profession. You can be onstage with live other people, but you’re still alone in some way. It’s as if you’re stripped naked. It’s frightening, but at the same time you get this feeling of exhilaration.”

Sean and! became friends. One time I asked if he wanted to be a professional actor. Sean laughed. “Are you crazy?” he replied. “Do you know what kind of life that would be?”

Nearly twenty years later, I was walking by a Broadway theater in New York City one night, when a large photograph of the cast caught my attention. There, among the other actors, was the familiar face of Sean Griffin. My God, I thought, has Sean been an actor all these years? He’s on Broadway!

The stage door opened and Sean and I stood facing each other for the first time in two decades.

He was basically unchanged, although his brogue was gone. I was startled to learn that he had appeared on Broadway three other times. And that he had acted in popular TV shows such as Starsky and Hutch, Barnaby Jones, Columbo and a string of daytime soap operas.

“From the beginning,” he said, “I knew it wasn’t going to be easy. I just kept working and learning. Just tried to get better at what I was doing.”

As Sean spoke, he revealed how tough it had been to survive as an actor. He had waited on tables, made the rounds of casting agents and auditions, faced rejection over and over. And yet, because of his past, the idea of quitting never occurred to him.

“I was married for seven years,” he told me, “but all the ups and downs took their toll on my family life. Rehearsing, traveling, often gone for months. Marriage is difficult enough, but when you’re separated so much…”

A few years ago, Sean decided to return to regional theaters, where he has appeared in one play after another. “The important thing for me is to be working,” he explained one night. “Eighty-five per cent of the actors in New York and Hollywood are unemployed. The top people make millions but, on average, an actor’s yearly income is $4000. Maybe less.”

Sean has steadily earned his living by living steadily out of a suitcase, making at best about $14,000 a year. In 1985, he toured with Cyrano de Bergerac to 47 towns and cities. That fall, Sean performed in South Bend, where his parents still live. I flew out there and joined him.

We visited the Notre Dame Theater Department, where Sean – their “returning hero”- told the students: “If you don’t have the drive, forget it. You need a bit of healthy insanity. If you don’t have that, do something else.”

I joined Sean at his parents’ house for a family meal. Amid the good-natured irreverence and laughter, I began to realize that here was the real secret inside Sean. Here was his wellspring of love and warmth and support.

Cyrano is about an uncomely man who is mocked and scorned. But inside, this is no ordinary man. He has, within him, that “bit of healthy insanity” and, by the end of the play, he also embodies the highest ideals of love, courage, integrity and the magnificent possibilities of the human spirit.

Sean played LeBret, the only man who understands Cyrano. At one point, he was left alone onstage, standing midway up a giant staircase. His gaze swept the South Bend audience until he seemed to be staring directly at his father and mother, sending them a silent message:

“I’ve gone a long way, to come back on my own terms. Thank you for understanding. I’m home up here. This is who I am.”

===============

Sean lives in Seattle (where he’s also a recognized artist as a painter!) with his wonderful wife Bernadine (Bernie) C. Griffin, who is currently Director of Theater Advancement and Development at the historic 5th Avenue Theatre in Seattle (and, so I hear, soon to be the new Managing Director).

Here’s from of another rave review of Sean in The Seafarer:

“You could feel it. Sometimes the audience just want a play to end so they can get out of there. Last night the audience wanted the play to end for an entirely different reason. They wanted to applaud the hell out of Sean G Griffin. The rest of the cast were pretty good too but Griffin as irascible old codger, Richard Harkin, dominated the stage from start to finish … Prost Amerika has reviewed many shows at the Rep but can honestly say that Griffin’s portrayal of Richard Harkin was the most dominating single performance we have seen here.”

Keep up the great work, Sean!