The following is a report I wrote for PARADE in 1992 on the leader Paiakan of the Kayapo people of the Amazon rain forest. [Barbara Pyle, one of the world’s foremost environmental leaders in the fight to save the planet, made my trip possible.] If anyone would like to give us an update, please do! I’ll get back here sooner than later with what I can learn about subsequent events over the past eighteen years.

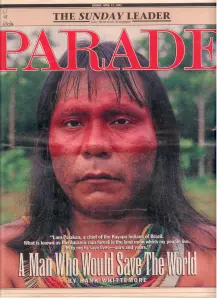

PARADE – A MAN WHO WOULD SAVE THE WORLD

April 12, 1992

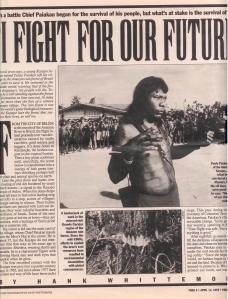

By Hank Whittemore

Parade Magazine - April 12, 1992 - Paiakan, chief of the Kayapo Indians of Brazil - Photo by Hank Whittemore

Several years ago, a young Kayapo Indian named Paulo Paiakan left his village in the Amazon rain forest of Brazil in order to save it. He ventured to the outside world, warning that if the forest disappears, his people will die. Today he is still standing against the forces of destruction as time runs out. At stake is far more than the fate of a remote Kayapo village. The rain forest is one of the world’s great biological treasures.

If the Kayapo lose the forest that sustains their lives, so will we.

From the City of Belem at the mouth of the Amazon River in Brazil, the flight inland proceeds over vast devastation caused by cattle ranchers, gold miners and loggers. It’s three hours to Rendenção, the farthest outpost on the tropical frontier. Then a tiny plane continues until, mercifully, the scene below is transformed into a canopy of lush green treetops shielding perhaps half the plant and animal species on earth.

Later the pilot dives and banks over a clearing of red dirt bordered by small thatch homes – a signal to the Kayapo people of Aukre. When the plane drops amid tall trees to find a thin landing strip and rolls to a stop, scores of villagers emerge staring in silence. Their bodies and faces are painted with intricate de signs; they wear colorful bracelets and necklaces of beads. Some of the men carry guns or knives or bows – they are warriors, with a heritage of fierce pride that is centuries old.

The visitor is led into the main yard of the village, where Chief Paiakan stands near the Men’s Hut at the center. He is about 37, but the Kayapo do not measure time that way, so his exact age is unknown. Shirtless, wearing shorts and sandals, he is a charismatic figure with flowing black hair and dark eyes that sparkle when he grins.

The first recorded contact with the Kayapo was just over a quarter century ago, in 1965, and since about 1977 their culture and way of life have been under siege. This year, during the 500th anniversary of Columbus’ first contact with the Americas, Paiakan’s village faces irrevocable change. Yet he greets the visitor warmly, speaking in Portuguese:

“Your flight was safe. You are here. Everything is good.”

After nightfall, as sounds of the forest fill the darkness, a Kayapo elder points to the stars and observes that they are distant campfires. Paiakan rests in a hammock under the roof outside his house, speaking softly:

“Since the beginning of the world, we Indians began to love the forest and the land. Because of this, we have learned to preserve it. We are trying to protect our lands, our traditions, our knowledge. We defend to not destroy. If there was no forest, there would be no Indians.”

Rain forests are vital for the rest of us as well. Because they absorb carbon dioxide and emit oxygen into the atmosphere, rain-forest destruction affects weather patterns and contributes to global warming, the so-called Greenhouse Effect. Furthermore, half of the world’s biogenetic diversity is within these tropical forests, yet 50 percent of those species are still unknown to the outside world. About one third of the world’s medicines come from tropical plants, but indigenous people like the Kayapo have even more knowledge of plants with curative powers – knowledge that is quickly vanishing along with the forests themselves.

Among the Kayapo, preparation for a new leader begins at birth. Such was the case for Paiakan, who is descended from a long line of chiefs. His father, Chiciri, who lives in Aukre, is a highly regarded peacemaker, and when Paiakan was born, the tribe received a “vision” of his special destiny.

“When I was still a boy,” Paiakan recalls, “I knew that one day I would go out into the world to learn what was coming to us.”

As a teenager, Paiakan got his chance. He was sent to the Kayapo village of Gorotire for missionary school, where he met white men who were building the Trans-Amazonian Highway through the jungle. Paiakan was recruited to go out ahead of the road’s progress, to approach the previously un-contacted tribes.

When he went back to see what was coming on the road, however, he saw an invasion of ranchers, miners and loggers using fires and chainsaws. As he watched them tearing down vast tracts of forest and polluting the rivers with mercury, he realized that his actual job was to “pacify” other Indians into accepting it.

“I stopped working for the white man,” he says, “and went back to my village. I told my people, ‘They are cutting down the trees with big machines. They are killing the land and spoiling the river. They are great animals bringing great problems for us.’ I told them we must leave, to get away from the threats.”

Paiakan (center) with Sting, who has been a continuing supporter of the Kayapo. Photo by Sue Cunningham

Most of the Kayapo villagers did not believe him, arguing that the forest was

indestructible. So Paiakan formed a splinter group of about 150 men, women and children who agreed to move farther away. For the next two years, advance parties went ahead to plant crops and build homes. In 1983, they traveled four days together, 180 miles downriver, and settled in Aukre.

“Our life is better here,” Paiakan says, “because this place is very rich in fish and game, with good soil. Our real name is Mebengokre – ‘people of the water’s source.’ The river is life for the plants and animals, as well as for the Indian.”

But the new security did not last. During the 1980s, most other Kayapo villages in the Amazon were severely affected by the relentless invasions. Along with polluted air and water came out breaks of new diseases, requiring modern medicines for treatment. Aukre was still safe, but smoke from burning forests already could be seen and smelled. Paiakan, realizing that he could not run forever, made a courageous decision. He would leave his people again –this time to go fight for them.

He went to Belem, the state capital where he learned to live, dress and a like a white man. He learned to speak Portuguese, in order to communicate with government officials. He even taught himself to use a video camera, to document the destruction of the forest – so his people could see it for rainforest themselves and so the Kayapo children would know about it.

Paiakan continued to travel between Aukre and the modern world, at one point becoming a government adviser on indigenous affairs for the Amazon. In 1988, when the rubber tapper Chico Mendes was shot dead by ranchers for organizing grass-roots resistance to deforestation, it was feared that Paiakan himself might be a target.

“Many indigenous leaders have been killed,” says Darrell Posey, an ethno-biologist from Kentucky who has worked with the Indians of Brazil for 15 years, “but publicity surrounding the Mendes murder may have helped to protect Paiakan.” The Brazilian Pastoral Commission for Land has counted more than 1200 murders of activist peasants, union leaders, priests and lawyers in the past decade.

In 1988, after speaking out against a proposed hydroelectric dam in the rain forest, both Paiakan and Posey were charged with breaking a Brazilian law against “foreigners” criticizing the government. Because Indians are not legally citizens, Paiakan faced three years in prison and expulsion from the country; but when other Kayapo learned of his plight, some 400 leaders emerged from the forest in war paint. The charges were dropped.

“In the old days,” Paiakan told the press, “my people were great warriors. We were afraid of nothing. We are still not afraid of anything. But now, instead of war clubs, we are using words. And I had to come out, to tell you that by destroying our environment, you’re destroying your own. If I didn’t come out, you wouldn’t know what you’re doing.”

In 1989, Paiakan organized an historic gathering in Altamira, Brazil, that brought together Indians and members of the environmental movement. A major theme of the conference was that protecting natural resources involves using the traditional knowledge of indigenous peoples.

“If you want to save the rain forest,” he said, “you have to take into account the people who live there.”

With increasing support, Paiakan acquired a small plane for flying to and from his village. He also made trips to the United States, Europe and Japan, even touring briefly with the rock star Sting [see photo above] to make speeches about the growing urgency of his people’s plight.

But the erosion of Indian culture in the Amazon forest was becoming pervasive. With the influx of goods ranging from medicines to flashlights to radios to refrigerators to hunting gear, village after village was succumbing to internal pressure for money to buy more. By1990, only Aukre and one other Kayapo community had refused to sell their tree-cutting rights to the loggers, whose tactics included seductive offers of material goods to Indian leaders.

In June that year, racing against time, Paiakan completed negotiations for Aukre to make its own money while preserving the forest. Working with The Body Shop, an organic-cosmetics chain based in Britain, he arranged for villagers to harvest Brazil nuts and then create a natural oil used in hair conditioners. It would be their first product for export.

Paiakan returned with his triumphant news only to learn that other leaders of Aukre – during the previous month, in his absence – had sold the village’s timber rights for two years. It was a crushing blow, causing him to exclaim that all his “talking to the world” had been in vain. He said that if he could not save his people, he would rather not live.

“He went through a period of intense, deep pain,” says Saulo Petian, a Brazilian from Sao Paulo employed by The Body Shop to work with the Kayapo. “He left the village and went far along the river, to be by himself. After about two months, when he got over his sadness and resentment, he came back and told me, ‘Well, I traveled around the world and seemed to

be successful, but the concrete results for the village were very little. These are my people. They have many needs. I can’t go against them now.”

So Paiakan made peace with the other leaders of his village and started over.

“I was like a man running along but who got tired and stopped to rest,” Paiakan recalls. “Then I came back, to continue my fight into the future.”

What began was the simultaneous unfolding of two events, by opposing forces, in Paiakan’s village. One was the beginning of construction by the Indians of a small “factory” with a palm-leaf roof for creation of the hair-conditioning oil. For Paiakan it was a way of showing his people how to earn money from the forest without allowing it to be destroyed.

Meanwhile, loggers came through the forest constructing a road that skirted the edge of the village. By 1991, trucks were arriving from the frontier to carry back loads of freshly cut timber.

The white men left behind the first outbreak of malaria that Aukre had seen, mainly afflicting the elders and children. The only consolation for Paiakan was that the tree-cutters had just a couple of dry months each year when the road was passable.

“Through the Brazil-nut oil project,” Petian says, “Paiakan is showing his people another possibility for satisfying their economic needs. He’s giving them a viable alternative that includes helping to save the forest and their way of life.”

Throughout Brazil, there is similar effort by environmentalists and Indian groups to discourage deforestation by creating markets for nuts, roots, fruits, oils, pigments and essences that can be regularly harvested. Since 1990, about a dozen products using ingredients from the Brazilian Amazon have entered the American market. The nuts, for example, are being used to produce a brittle candy called Rainforest Crunch. The candy is also used by Ben & Jerry’s Homemade Inc. for one of its ice cream flavors.

“Paiakan is one of the most important leaders looking at alternatives for sustainable development,” says Stephan Schwartz- man, a rain-forest expert at the Environmental Defense Fund in Washington, D.C. He cautions, however, that “nothing in the short term can compete economically” with cash from the sale of tights for logging and gold mining.

Up to 8 percent of the two million square mile Amazon rain forest in Brazil – an area about the size of California – already has been deforested. Once the trees are gone, the topsoil is quickly and irreversibly eroded, so that in just a few years hardly anything can grow, and both cattle-raising and agriculture become nearly impossible.

A hopeful sign is that Brazil’s president, Fernando Collorde Mello, who took office in 1990, has taken some positive steps to protect both the forest and the Indians. (The population of indigenous people in Brazil, once at least 3. million, has fallen this century to 225,000.) Last November, President Collor moved to reserve more than 36,000 square miles of Amazon rain forest as a homeland for an estimated 9000 Yanomami Indians in Brazil. He also approved 71 other reserves covering 42,471 square miles, some 19,000 of

which will be set aside for the Kayapo – about 4000 people in a dozen villages.

It was a major victory for Paiakan, giving him more concrete evidence to show that his efforts outside the village had been worthwhile.

“Paiakan has a vision,” Darrell Posey says. “He’s trying in lots of ways to maintain his traditions—setting up a village school for Kayapo culture, creating a scientific reserve. At the same time, he’s making the transition to a modem world in which white men are not going to go away. He knows you either deal with them or you don’t survive.”

These days, Paiakan is working to organize an Earth Parliament of indigenous leaders in Rio tie Janeiro in June. The global parliament will run simultaneously with the UN Conference on Environment and Development, the so- called Earth Summit, which more than 70 percent of the world’s heads of state are expected to attend to ponder the fate of the planet.

[Tonight, the TBS program Network Earth will focus on Paiakan and the Kayapo fight to save their forest.]

“Paiakan has been at the center of incredible change, whether he has wanted to be or not,” Posey says, “and now he’s trying to straddle both the past and the future. I would hope that people in positions of power will see him as someone who can help the world turn back to its roots, to those whose lives depend on working with nature and not against it.”

The Rainforest itself has taken on tremendous symbolic value worldwide, says Thomas Lovejoy, a leading Amazon researcher and assistant secretary for external affairs of the Smithsonian Institution.” It’s a metaphor for the entire global crisis,” Lovejoy adds. “If we can’t deal with that environment and with the people who live there properly, it’s unlikely that we’ll be able to deal with the rest.”

At sunrise in the Kayapo village of Aukre, the red clay of the logging road is wet from rain. The trucks are gone, now, and there is serenity as the tropical heat moves in. A shaman, or medicine man, is treating Paiakan’s wife for an illness, using plants from the “pharmacy” of the forest. Some of the men are going off on a hunting trip. Women and children bathe in the river as butterflies of brilliant colors swirl across a blue sky.

Time seems to stand still, before it races on.